This summer I went along to the launch of the book, There Is No Word For It, a series of short “monologues from the trans man community, exploring childhood to manhood, sex and sexuality” and is by Laura Bridgeman and Serge Nicholson. There Is No Word For It is based on a theatre project, the (Trans) Mangina Monologues, which was staged and devised by Laura and Serge in 2009. Directed by Lois Weaver, with Simon Croft designing the visuals, the (Trans) Mangina Monologues, was a unique piece of live theatre featuring a cast of trans men sharing their stories of the trans guy experience on stage.

This attractively designed and produced 110-page book (which reminded me very much of the US-based Semiotexte publications) has been compiled, written and edited by Serge and Laura and is the first book on their Hotpencil Press imprint and costs £12.99.

The book covers various aspects of the experiences of 12 trans men across south-east Asia, the UK and France who contributed their stories firstly to the (Trans) Mangina Monologues, and which now appear in There Is No Word For It. The book is comprised of 12 chapters – with titles ranging from “Childhood and family”, “Transitioning bodies”, “From low to gung-ho”, “Male privilege”, “Medical settings” and “Sex (part one)”.

There Is No Word For It is simple and spare in its content and presentation (and all the better for it). It is a sensitive, honest, non-sensational, provocative and fascinating account of an experience which, if discussed at all, is usually in a prurient, sometimes trivialised, lurid manner. It’s also funny and pretty damn sexy too.

This autumn, I talked to Serge and Laura about the (Trans) Mangina Monologues and There Is No Word For It.

FS: Where did you both meet?

The cover of There Is No Word For It

SN: Probably through First Out coffee shop which was like LGBT finishing school. Everyone’s worked there, from Graham Norton to Amy Lamé. I worked there 19-20 years ago.

LB: I was doing stuff for the Transfabulous festival [of which Serge is a co-founder] wasn’t I? We just started hanging out and I remember we were in your flat and you said that you had this idea to do the Trans (Mangina) Monologues, a version of the Vagina Monologues with a cast of trans guys. I just looked it you said that’s a fantastic brilliant idea. This was properly four years ago.

SN: We would be in the middle of the Transfabulous festival

FS: What’s the Transfabulous festival?

SN: The Transfabulous Arts Festival ran from 2005 until 2008 with three international festivals of International transgender artists and artists of interest to transgender people. We did three summers at Oxford House in Bethnal Green. It was a full packed-out festival programme that was completely sold-out. It was always a summer weekend with performance nights, spoken word workshops. Laura and re-met there and Laura came and did stuff there. So by the 2008 Festival, we had had the idea for the monologues. We started to test and collect stories. We had talking booths in the gallery at Oxford House to see if people would to see if people would like the idea and share stuff with us that easily. We tested it there, and then after the festival ended, we knew we’d got something and we could really go and advertise for trans-masculine people to come to us.

I think if you didn’t know about the Transfabulous effect, not only was it an arts experience,but over those years, it also broke down a lot of barriers. So that lots of people could work together and attend work together. So in terms of trans women and trans men, partners, friends, gender-queers, queer people, butch dykes, it could be possible that we were all there together. And that also quite a few love affairs started at those festivals as well. And things have shifted a lot in terms of how people understand each other, dare to approach each other. so that’s also part of what happened because of Transfabulous.

LB: Yes, you created a dynamic space – quite an unusual space as well – all encompassing as well.

FS: (To LB) You’re a performer. Is that your background?

LB: Yes I went to drama school then I left and worked with lots of writers in theatre companies. Then I formed my own theatre company.

FS: What did your theatre company specialise in?

LB: I did some performance art events and the last big thing I did was when I got some money from the London Arts Board (as it was at the time). I did a production for the Battersea Arts venue in a site specific venue, a disused dance hall in Clapham Junction. I curated the show and wrote it. This was the last big thing I did. And post then I started to get commissions from Radio 4 and from other theatre companies to write for them. The writing took off and the performing dropped away.

FS: So you were writing plays?

LB: Yes, writing plays more – more traditional work. Then I went to University of East Anglia where I did a MA and PhD and turned to prose. And this project is kind of a mix of the two. It started off as a theatre show with a script and the publication felt more of a prose piece that exists within its own right. I had my own company for a while.

FS: What was that called?

LB: Art Throb, then I changed it to Girlboy. I started to work with Michael Atavar on some projects together and we affiliated ourselves. After this, the writing took off and I started to be commissioned. I wasn’t performing so much but then through Transfabulous I started to do a little more live art and the tiny bit more writing and performing. Then Serge approached me to do this and it just built.

FS: (To SN) Do you have a performance background?

SN: I did two Gay Shames at Duckie. I’ve also done things with Transfabulous – things to do with trans masculine visibility. So Jason and I did the F-to-M Full Monty – which almost caused a riot. It brought the house down. This took place at the Pleasure Unit in Bethnal Green Road. Somehow, the council got wind of it and some inspectors came down and said we couldn’t strip. If we didn’t do it however, it would have brought the house down. So we just had to do it – quickly – and it was absolutely riotous, with screaming like Beatlemania. It was done very much like the Full Monty with hardhats, so you weren’t really exposing yourself. We also went on to do the Puppetry of the Phalloplasty which was about going to the Charing Cross gender clinic and all the hurdles you have to jump over. And it was about all these horrible psychiatrists who are power mad that you have to see. So we did these two pieces which were humorous but were working with stuff that everyone really wanted to see. And in the Puppetry of the Phalloplasty, we had a puppet cock that actually shot milk – it was gross.

Serge Nicholson (left) and Laura Bridgeman (right) at the launch for There Is No Word For It

FS: So you started with the talking booth at Oxford House and you saw that people were open and they wanted to talk.

SN: Only within the safety of Transfabulous – where we really took over the whole venue. There was also that sense of integrity behind what I was setting out to do. I was known as someone doing transgender activism through the arts. So I already had the trust of people. We couldn’t have just set it up in an ordinary arts space. Oxford House was now our home and people knew us. It was the right kind of safe playspace for people to come and speak to us. We were us just testing out the idea for the future and it worked.

FS: When was that?

SN: In the 2008 arts festival weekend.

FS: And the actual (Trans) Mangina Monologues were performed in 2009? So you got 12 people together who wanted to collaborate with you?

SN: Yes.

FS: So did people write down their stories or did you interview them?

LB: No, a few people wrote stuff. When contributors were based quite far away, we asked them to write down material. Serge and I went out individually and talked to people, gathering hours and hours of transcription. At the beginning, we didn’t lead or guide it, we just let people speak as we weren’t sure of the shape of the show – whether we were going to cut the monologues up. However, as we went on, it seemed as there were areas where people’s journeys cross-referenced. Then we started to cut our material into the sections. By the time we were taking the latter transcripts, with the last few contributors, we decided which sections worked. We were able to guide it a bit more.

FS: I think the book is great because there’s all these different aspects, different angles and different elements that I would never have thought of. It’s very beautifully and sensitively done – good-humoured and very intuitive. It’s entertaining. There are many insights, into a subject that usually sensationalised – if it’s ever dealt with at all.

SN: I think the humour is part of a survival armour. It is essential really to not get defeated.

FS: And the book does contain the best riposte ever. One of the contributors describes how to deal with any insults one may encounter with, “You’ve really got to work harder on your chat up lines”. You said in the book that you had evolved three general headings.

LB: We wrote down lots of stuff we had sheets of wallpaper.

SN: With all of our scrawls all over it.

LB: If you go through the material looking at childhood and family, and what the contributors’ backgrounds were like, it seemed to be that people didn’t feel like they belonged, as other kids did at school, or in the family environment, and during the teenage years where your sexual preferences might have developed. And then the material moved on to sexuality and re-addressing sexuality; and then the journey might be about gender. It seems to be the beginnings of people’s backgrounds were obviously very different, and, then, what was interesting for us was people’s transitions and dealings with the medical services. In this respect, the experience of people living abroad was very different to people living in the UK. It seemed to us that we should include those stories in. We had one contributor who was based in Europe during transition and another one who was in Australia. So it was actually compare and contrast.

SN: What we were looking for also was a certain British voice – whether the contributors were living here, and had been here for some time, or they were living in other countries. We were looking for UK backgrounds rather than US ones. I think that worked very well so even though Americans might have some difficulty with some of the slang and the jokes and the language.

Serge Nicholson. Photograph byJamie Mcleod

FS: But you have a handy glossary at the back of the book.

SN: But in terms of the humour.

FS: The British sense of humour?

SN: We also wanted to cover people from quite a few different regions of Britain and then, to protect their anonymity, we switched things around a bit so that no one is going to stand out.

LB: We said to the guys from the beginning that, ultimately, you have the last call on what we will put in the script, and also publish. However, in the editing process, obviously things change – you may say things in the moment that you might not remember saying. So we always asked the contributors to approve the text before it went to the final draft. We took the transcripts and then we started to write them up and we weren’t sure initially how that was going to go. I did try with, the early passages to make them more poetical but it didn’t seem to work. So what I do now, which seems to be a stronger thing, or a more authentic thing, to try to get down word for word. We tried to keep very close to each person’s speaking voice.

FS: I really like this style. I think it’s really beautifully written.

LB: It’s quite conversational I think.

FS: I think there’s something very beautifully understated and poetic about it. I like its subtle little jokes

LB: We tried to keep that lightness of touch. Serge and I felt that would work well and not sort of over-egg the pudding. In the live piece, we had a lot of material and people felt we went at a cracking speed. However, some people wanted a little time to just sit with it and reabsorb it. Certainly, with a publication you can go back and revisit a story, or just take time with it let it filter down. I think the material from the performance lent itself quite naturally to publication.

FS: Were the performers some of the people who told you their stories?

LB: We can’t say that.

FS: But there are more people telling you their stories in the book than you had performers on the stage.

SN: Yes, in the same way what we found when you did perform a piece, people thought it was your story. Wherever you go, you have to bear this in mind.

Laura Bridgeman signing copies of There Is No Word For It at the launch

FS: Were the performers trained actors?

LB: No. What Serge and I decided to do was to actually keep it within the community, although some of the guys had had stage experience.

SN: Or the Transfabulous experience as well.

LB: But not everyone, and that’s why when we approached the director Lois Weaver who I thought would be a good person as she has worked with people who are not trained actors. I knew that she would just make everyone feel comfortable, confident and that worked well.

SN: Oh yes. It was a hugely empoweringly thing to be involved in it and also for the audience. They would never necessarily have seen five trans masculine people on stage together ever before.

LB: That’s true. We were worried. We debated it. I always said to Serge that I wanted to make the work, or the publication, or the experience, as inclusive as possible. So that is part of the reason we put the glossary in the book. We didn’t want to preach to the converted – nor want to alienate people. In fact, a heterosexual friend of mine came along who doesn’t really know much about this experience, and she said something quite poignant, “I am sitting here and gender affects you whether you are trans or not, gender affects you on a daily basis. I’m listening to these stories and it is involving and it is engaging for that reason”.We wanted that people could bring relatives along who don’t know much about the trans experience, but be able to get something from it.

SN: And that the friends and lovers are also part of the transition process and they will be audience members and so the work resonates.

LB: It’s like hidden histories.

SN: It was harder than we thought.

FS: That’s my next question. Is it easy or difficult to put on a show like this?

SN: It’s hard to get around the British reserve when you’re talking about sex. That was harder then we thought.

FS: What for the writers or the performers?

SN: No, the contributors. There were some people that were very much ease with it. But it was hard. I also think that is part of Britishness too.

LB: Essentially, if you offer up a story, it’s your story. So we never asked contributors to say something they didn’t feel comfortable with. But, by the end, we were saying we would welcome hearing about your sex life. But it was up to the person to draw their own line about what they felt comfortable. But actually looking back over the transcripts, Serge and I definitely saw a correlation with the guys that weren’t transitioning in the UK, and the guys that weren’t British, were open and more comfortable. I don’t know if was a coincidence – but they were more at ease. And what was different and interesting were that some guys were in the existing relationships before transition and guys that had started different relationships post-transition – all those sort of things that were quite fascinating for us as well.

FS: Was it hard to put the actual performance on or was the money easy to raise?

LB: We got some money from the Arts Council just prior to the cuts. But at one point because we couldn’t match-fund it in the way we anticipated, which was a conditions of the grant, as it was conditional. We didn’t get the funding that we thought we would. However, eventually we managed to put a package to them which they accepted. That was very tough. We had to have some stiff phone conversations with the Arts Council.

SN: We did feel as well that we were misunderstood.

Serge Nicholson. Photograph by Jamie Mcleod.

FS: In what way?

SN: Don’t know that they didn’t see …

LB: The relevance of it …

SN: They wanted something fluffy lesbian and gay loveliness. But anyway we won.

LB: And when we went to sell tickets for the performances at Queen Mary, University of London and the Soho Theatre, they had sold out. I have never worked on anything like that. So, actually, there is a massive audience and appetite for the work. And the book launch was the same again.

FS: There were a lot of people there.

LB: The time is now. Doing this work, I totally underestimated that appetite and I think Lois did as well.

SN: If only we had the book then …

LB: That’s true.

FS: So how many performances did you do?

LB: We did the two in London [mentioned above]. But on the back of the book, we are setting up more. Serge and I always had this idea that we would go around the country and collect new stories all the time and invite guys from those regions to join us on stage, if they wanted to contribute. This was more or less Eve Ensler’s idea with the Vagina Monologues which is always mutating and changing. We had the idea to do a sort of roadshow.

FS: Is there anything comparable with the (Trans) Mangina Monologues anywhere else in the world?

LB: We know it’s the largest piece of trans theatre work going on in Europe.

SN: I don’t think there’s anything else that can compare to this in terms of current voices and that is also something people could pick up and perform themselves. So I would really like to see someone take it and put it on. But in terms of just pieces that just stand up in their own right, and at readings, I think to do this in other countries or places, like San Francisco and New York, will be powerful. I don’t think there’s anything like it. Also as a collection it covers a really wide scope. We costed it.

LB: But it’s hard financially. So you have to go back to the Arts Council again. We went back to the drawing board. We realised that once you’ve got a product (ie a book) in your hand, you can get readings and shows booked off the back of that.

FS: You realised that a book was the next step?

LB: We priced it up we went to the Arts Council and tried to get money to publish the book.

FS: Did you get some lottery money?

LB: We got that originally for the show but nothing for the book in the end. And so we just thought we are going to do it anyway.

SN: We didn’t want it to disappear.

LB: Exactly. A few people who contacted us online to give us their story. One guy didn’t show up and another was going to do a telephone thing but they didn’t happen. So maybe they thought it’s not there anymore We did the two shows and now there is physically a product. This is in existence.

FS: What are your next plans?

LB: We we are trying to set ups some UK dates, potentially for Brighton Festival next year. And we’re doing an event with the Arnofini Gallery in Bristol. We are keen to take it to the US. We’ve had some interest from New York, where Lois is based, also San Francisco – potentially for Pride next year. But again we need to think about the costing and pricings.

SN: If we do develop this further, or we go onto the companion book of the lovers of trans masculine people, there has already been a shift in time and language. The glossary at the end of the book is out of date already. There will have been rapid changes.

LB: Very early on Serge said to me he was keen to get in the lovers’ voices. I said at the time that it’s properly going to be too big, I’d rather concentrate on the guys’ stories and just get those really solid and firm. And once we had that I do think there is a place for the lovers and partners and to get their stories told . We actually did some writing workshops up at the Central School of Speech and Drama with Jay Stewart’s company, Gender Intelligence and we worked with some of the trans youth group and other members of the public who wanted to come in.

FS: So are you pleased and satisfied with the results of the project?

LB: Yes.

FS: What have the responses been like? Are they all positive?

LB: Yes. And we would love to do more. Obviously, we have got people supporting us. Anyone who has read the publication has said it is fantastic or that they love a particular story. It just seems to be hitting a nerve. We are really happy. If we had more time or more money, we would do this full time. What Serge and I find hard about doing projects that are self-governed is that all your time and energy is taken up. You are doing everything. Of course you are doing all the artistic work. Serge was in the piece so he was on stage as well. And he was dealing with the technical side too. And it got to the point where we were actually selling the tickets too. And buying the beer for the party afterwards – we were doing everything. I really believe in the work and the project too. I think it is really needed. Theatre is sometimes accused of being elitist and not for the people. And I think this project counters all those accusations.

SN: Because there would be nothing for me or other guys to go and see like this. Or there would be nothing about sex. There was also a need that I could see. I feel that I wanted to read something like this.

LB: I suppose that in a way the book and the performance is quite political because it’s from the personal. I think we were only worried about changing the order [of the texts] when we did the stage show. Lois was quite keen to put the section on male privilege first. And we did do that although I said to Serge that I thought it was a mistake because then it looks like a series of statements – a bit soapboxy and heavy. In fact our idea was always to introduce people or have inclusivity. So actually when we went back to doing the book, I said I know childhood and family needs to go first because people step into the world as a child and everyone has a childhood.

SN: When trans people face psychiatric assessment, it always goes back to the family make-up and childhood. And in most films, or documentaries, there’s always that and it always goes into medical settings and surgery. We were trying to move on from that. But on the other hand, when it came to the book and accessibility, we fell back into that [pattern] as well.

LB: And I wondered about the logic of the order of the texts. And for me, it felt like having a timeline seemed the natural thing to do even though Serge’s point is right. It means that you can start with childhood and then you can go to things like male privilege, you’ve taken people, guided them into it. And when the show started with considering male privilege, I always felt that it began with something with something heavy and it’s best to start with something lighter.

FS: I think it’s very brave of you to address the issue of male privilege.

LB: Yes, and it’s quite easy to think it puts you on the back foot a bit.

FS: As what a trans person has to go through is so heavy anyway. It quite a brave thing to discuss.

LB: I think that it is sometimes thrown onto the trans male experience. There is an assumption that you’re going to be earning double, or your salary is going to increase, and all these things are going to fall into place because you’re no longer female. Actually all the stories were in counterpoint to that. I think that is an assumption that your life is going to get easier because you are presenting as male.

FS: One thing I liked in the book was how the trans men said they were happier because they’d lived both women’s and men’s lives and they weren’t frightened of getting old. I thought that was quite interesting – how the trans person experiences life from such different angles and points of view.

SN: The whole point of putting on the show was that the technicians and everyone involved was trans masculine, either in the show or the volunteers working with us. There was quite a large group of us and when we would go after rehearsals for a drink, Lois was surrounded by this adoring group of men, so she loved it. We love Lois. Lois loved us. It was a phenomenal experience. I also think now that it’s a different time and that there is now more people examining either that they feel gender queer or gender fluid. There’s more range of people forming their identities or fluid identities. Things have changed from maybe the old days of lesbians and dykes and trans not mixing together. I think times have just so changed and people can grow into themselves rather than being held back by community.

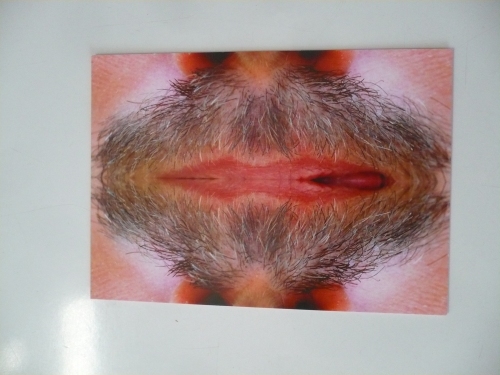

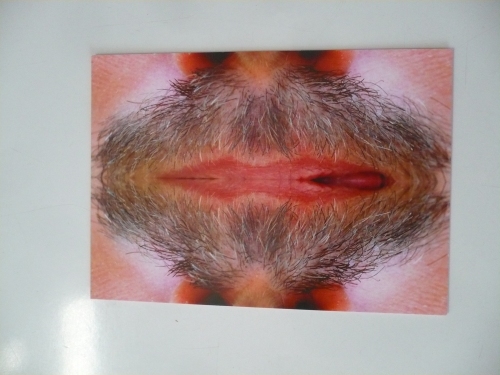

Which way up? The controversial image used for the postcards for the (Trans) Mangina Monologues (designed by Simon Croft)

LB: For us, the move from a theatre experience to a book encountering all those decisions you have to make when producing a publication. We had collaborated with the visual artist Simon Croft on the performances. It was also the first time he had ever worked on a book cover. We went so far ahead with ideas that they were too complex and had to come back. So it was very laborious but we still like its pleasing simple appearance. The title and credit font on the front cover is actually paper cuts.

And the postcard was an image that he made for us to promote the show. It was actually really controversial. So it’s only now that it is produced for the book with no type on the front cover of it. When it was first made the image was in a vertical position because of the position of the text and people would recoil – we had complaints. It’s a really powerful image and we just countered any complaints with the answer it’s just two moustachioed lips. It’s tongue in cheek and it’s really clever. Maybe too clever for some people.

Or this way? Tongue in cheek?

I’m so used to reading theatre texts and and plays. For me just the words on a page are what are important. I thought photographs would potentially weaken the book because sometimes when you’re offered the image, it takes away from the imagination. So I kind of felt we weren’t serving any purpose (in having images in the book). I said to Serge that we are so close to the material that we forget how strong the stories are. They are kind of like bombs going off your head and your hand. Actually I thought we would do a disservice to the work and the words. It would take away the power of the words.

FS: So was it a lot of work to edit all your material?

LB: It was just the thing of going over all the material. We added a more few stories too. We were paranoid that there might be a spelling mistake. At the end of the day, we couldn’t even look at it when it came out. We had reached that point. There were a lot of decisions to make. But I still believe in the power of the voices. And Serge is right – opinion, attitudes and experiences are changing the whole time.

SN: Nowadays, there are so many online groups about where you can share experiences. So times have really changed in terms of how you access information. On the other hand, I was thinking that the language has changed so rapidly that female-to-male and male-to-female are no longer going to be used, as some young people (and we learn a lot from them) say, “That’s not us. We were never female so we don’t want to be called one to the other”. Or in terms of using the phrase “trans masculine” this could be something used now but it could change again.

LB: Yes, that’s interesting and obviously the landscape is entirely changing with younger people growing up and, as you say, they have access to services that people of different generations just wouldn’t have had. However, again, I guess we are referring to people who are living in the metropolises in the West. I am still interested in flushing out the stories of people who are living in communities that more isolated. But we will see we are certainly up for still moving it on and doing other editions and seeing where it goes.

There is No Word for It is available at Gays the Word bookshop or via the Hotpencil press website http://www.hotpencilpress.com/

If you want to contact Serge and Laura, email them at: manginamonologues@live.com or, info@hotpencilpress.com

Hot Pencil Press also has a blog: http://pressthepencil.blogspot.com/

Many thanks to Laura and Serge for allowing me to interview them.

Credit: The phrase Genderful was coined by the wonderful Little Annie Bandez